Select Connection: INPUT[inlineListSuggester(optionQuery(#permanent_note), optionQuery(#literature_note), optionQuery(#fleeting_note)):connections]

Info

A Zettelkasten is a personal tool for thinking and writing. It has hypertextual features to make a web of thought possible. The difference to other systems is that you create a web of thoughts instead of notes of arbitrary size and form, and emphasize connection, not a collection.

Introduction

This method I’m about to present originates from a personal need to streamline the writing process with a rigorous organization to help me make the notes useful. As you will discover yourself, Zettelkasten is much more than that: it is a system you can rely, so to let your brain let go and let you focus on the task at hand, while also enabling a new way of thinking.

Zettelkasten is established on the concept on writing while learning. Writing in itself has a double purpose:

- helping understand and solidify content, only when we write down concepts we can link them and find holes in our knowledge. In our disorganized and chaotic mind, everything seems to make sense, but only when we are free of the burden of storing the knowledge we have the cognitive resources to see the full picture

- reducing work, while we learn we also build up resources for the future. Another pillar of the zettelkasten is connection: notes are not islands by themself, but they are embedded in a large network that mimic the structure of our brain.

To sum up, a short description is:

A Zettelkasten is a personal tool for thinking and writing. It has hypertextual features to make a web of thought possible. The difference to other systems is that you create a web of thoughts instead of notes of arbitrary size and form, and emphasize connection, not a collection. [1]

The origin of the method can be traced back to Niklas Luhmann, a law degree graduate converted to sociology. This switch in career was actually led by his slip-box method: thanks to it, he put together a doctoral thesis and the habilitation thesis in less than a year, while taking classes in sociology. After becoming professor at the University of Bielefeld, he published 50 books and over 600 articles, and after his death more than 150 unfinished manuscripts were found. His prolificacy can be attributed to the slip-box, which became his “dialogue partner, main idea generator and productivity engine”.

The Method

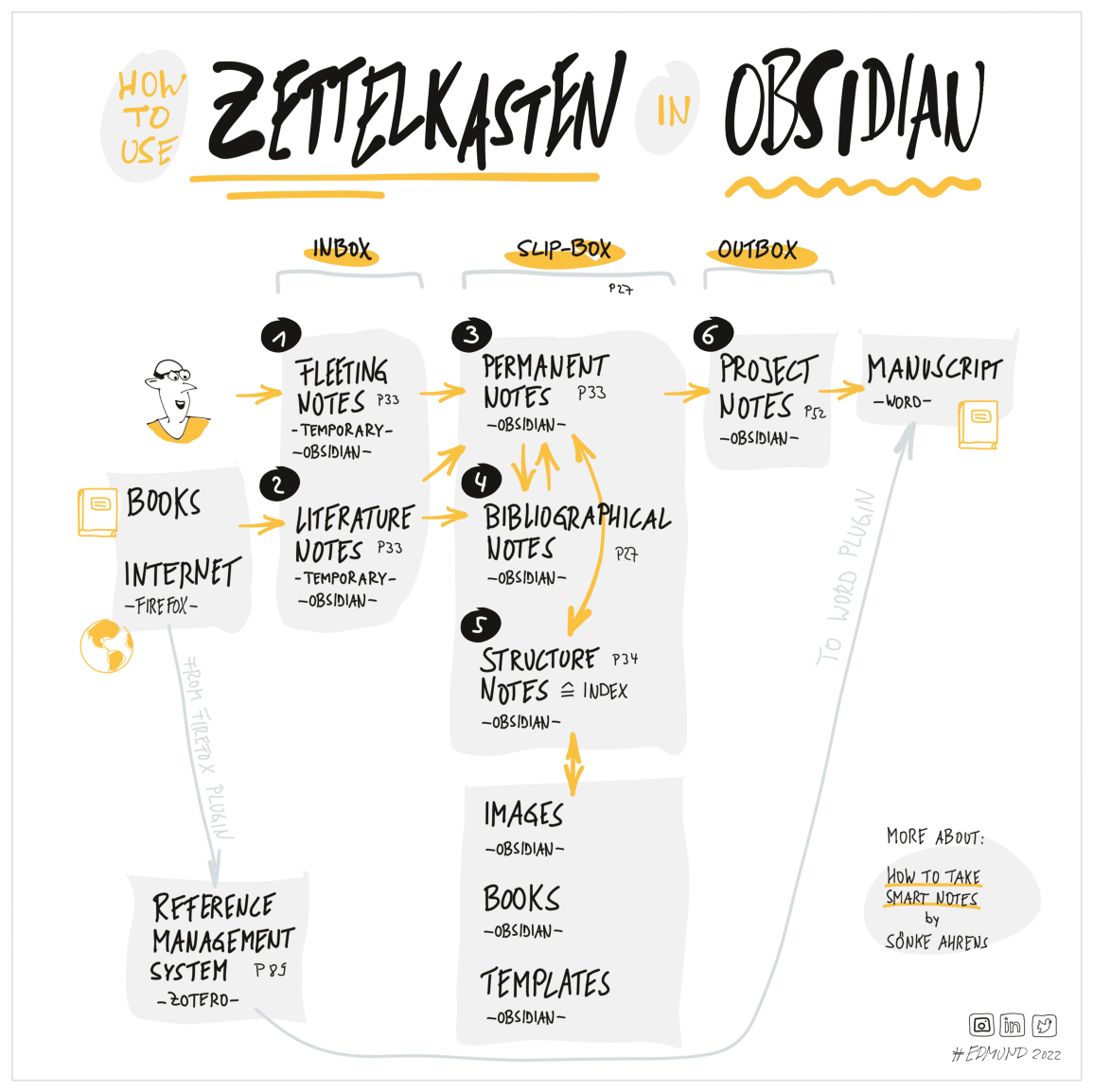

Figure 1: Workflow of the Zettelkasten. Reference: [2]

Notes should be split in three different folders:

- Fleeting, which contains unorganized and temporary notes which are meant to be deleted. Usually they are used to capture quick thoughts or ideas while doing something else. Review them daily.

- Literature, notes about what you read, be selective and write only what you think you’ll need. Also, don’t copy, but re-elaborate them to understand the concepts more clearly.

- Permanent, take notes from the first two steps and try to relate them to your thinking, write questions and new ideas that generate. Write one idea per note and as if you are writing for someone else, so make references, write full sentences and be as precise as possible. Actually in Figure 1 there are more note types, but this three are the main ones.

With this organization the workflow looks something like this:

- write fleeting and literature notes when you need it

- combine fleeting and literature notes in permanent notes

- add permanent notes to the slip-box by:

- putting them behind one or more related notes

- linking related notes

- making it accessible by writing it in the main index or in a topic index which is itself linked in the main index

- develop the notes further

- when you have enough developed ideas, write about some topic and write a draft

- edit and proofread the manuscript

Principles

To create a truly effective system, having a good workflow is just the beginning. It’s equally important to establish clear guiding principles that keep the method structured, scalable, and adaptable over time.

First Principle: Writing is the only thing that matters

Following this principle puts you in a deliberate state of mind since you need to rewrite in your own words what you are reading, and deliberate practice is the only way to improve in what you are doing. It also puts you in an active scenario, much different from the passive one we are used to have in school.

Second Principle: Simplicity is paramount

The structure described in the previous chapter is straightforward, keep it that way and don’t overcomplicate it.

Third Principle: Nobody ever starts from scratch

Writing is not a linear process, we will not be guided by a blindly made-up plan but by our interest, curiosity and intuition, which is formed and informed by the actual work of reading, thinking, discussing, writing and developing ideas, and is something that continuously grows and reflects our knowledge and understanding externally. This is the same concept as the hermeneutic circle.

Fourth Principle: Let the work carry you forward

TODO

Back Matter

Source

- based_on::How to Take Smart Notes - Sönke Ahrens

References [1]: https://zettelkasten.de/introduction/ [2]: https://medium.com/@groepl/take-useful-notes-use-unlimited-zettelkasten-practices-ac683a698ab8